The Santos Scandal: A Deep Dive into Deception (Part 1)

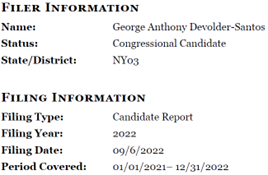

The congressional candidate’s website said he briefly attended an elite private school in the Bronx, New York. His campaign literature said he worked at Goldman Sachs and Citigroup. In a required financial disclosure form filed five months before his failed 2020 election attempt, he claimed his earned income in 2019 consisted of a $55,000 salary. It listed no assets, bank or checking accounts, investments, or properties. Somehow, however, according to his filings with the Federal Election Commission (FEC), he loaned his campaign $23,850 in 2019 and an additional $57,400 in early 2020.

The following year, in April 2021, a company he started working at in January 2020 was hit by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) with an “emergency action to stop an ongoing, fraudulent Ponzi-scheme victimizing hundreds of investors across the United States.” By 2022, according to a Congressional filing related to his second election bid, his financial wellbeing had nonetheless improved tremendously. His annual salary had risen to $750,000, and his “unearned” income leapt to between $1 million and $5 million for that year, while his assets had skyrocketed to between $2.6 million and $11.3 million.

George Anthony Devolder Santos (“George Santos”) is now well known, and the target of a 13-count criminal indictment by the Department of Justice that includes seven counts of wire fraud, three counts of money laundering, one count of theft of public funds, and two counts of making materially false statements to the U.S. House of Representatives. He has pleaded not guilty. However, his past appears to be catching up with him.

It should have happened much sooner. The falsehoods, distortions, and trail of misconduct surrounding Santos should have resulted in an avalanche of scrutiny well before it did. While a glimmer of the troubles surfaced in the local Long Island, New York, newspaper, the North Shore Leader two months before the 2022 election, the gravity and scale of his falsehoods did not come to light until one month after the election, when the New York Times published a detailed account of his fabrications. In short, the press, both main political parties, and public officials all failed to conduct a proper due diligence probe of him before the November 2022 election.

The George Santos saga thus provides a valuable lesson not only for politics but for investigative practices – and in particular, how public records can help reveal red flags. This is the first of three posts to be published in the coming days that will detail how such a review would have been able to unmask the mirage Santos projected before the November 2022 elections. Scrutinizing available public records would have revealed:

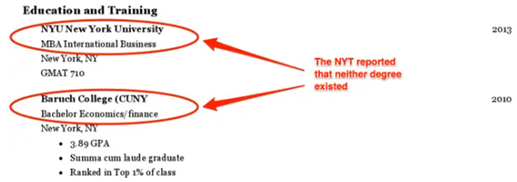

- Falsehoods in Santos’ public educational claims, by checking his educational record;

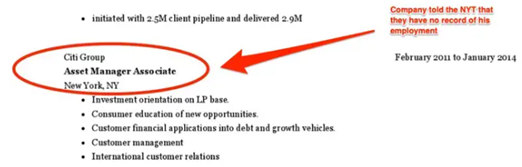

- Fabrications in his stated professional experience, through a review of public sources;

- Serious questions about the origin of the more than $700,000 he personally loaned his own campaign in both the 2020 and 2022 election cycle, based on FEC records;

- Questions regarding his unexplained sudden personal financial success in 2022, based on Congressional financial disclosure documents;

- Clear connections between Santos and multiple individuals who started companies in Florida days after the SEC’s “emergency action” against his former employer.

Part 1: A Litany of Lies

George Santos announced his first run for Congress in November 2019, as a Republican candidate. He lost the election to Thomas Suozzi the Democratic incumbent of New York’s 3rd congressional district, but he ran again in the 2022 election cycle. From the very start, his campaign website listed distortions and fabrications that could have been quickly and easily verified to be false.

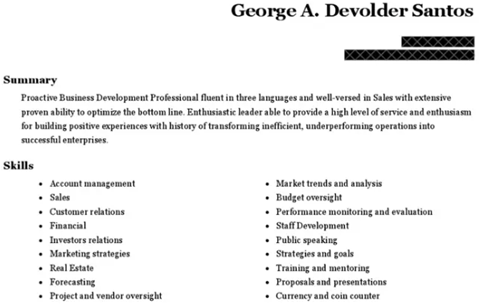

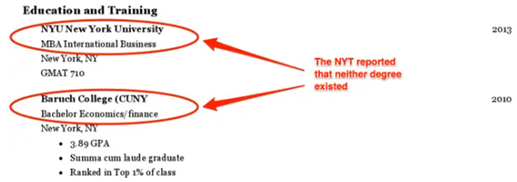

An annotated version of his resume, first released by the New York Times, was published by Business Insider, and is provided below.

Whether you are vetting a potential employee, senior executive, or attempting to learn more about a competitor or political candidate, resumes are a critical starting point for an investigation. Vetting claims can help to identify exaggerations, outright falsehoods, and character issues that provide key insights and future paths for further analysis.

Financial Flimflam

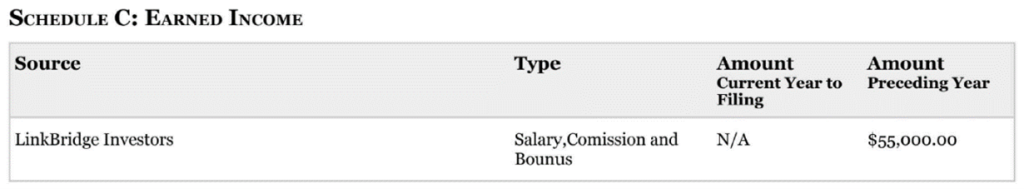

Records that show an implausible personal trajectory are among the most obvious red flags. On May 11, 2020, for example, Santos filed a required financial disclosure report to the House Committee on Ethics. Under the “Earned Income” section, he indicated that his salary, commission, and bonus at LinkBridge Investors in 2019 was $55,000.

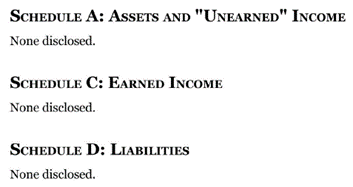

Although required to be fully disclosed, under “Assets and “Unearned” Income,” “Earned Income” and “Liabilities,” he wrote: “None disclosed.”

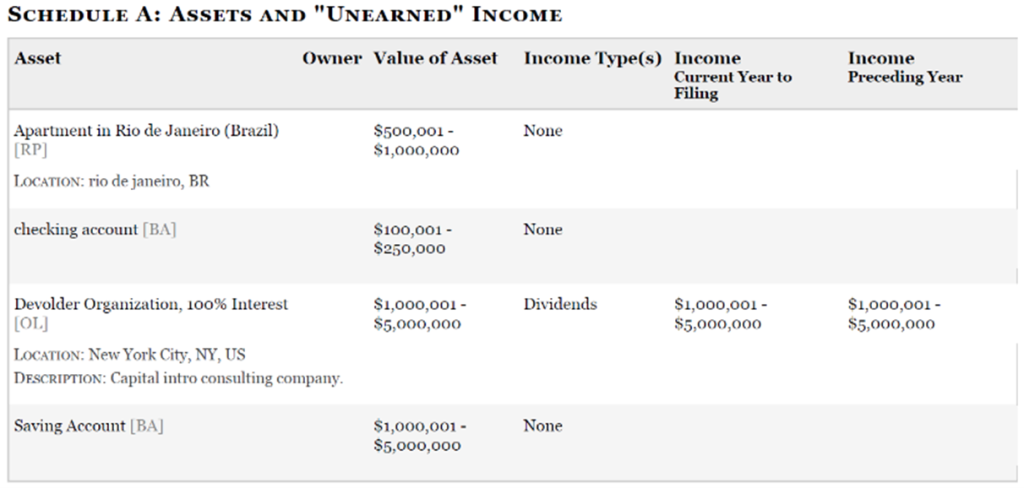

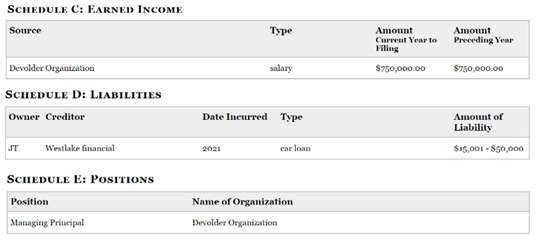

On September 6, 2022, during his second run for Congress, Santos filed his second Congressional financial disclosure report. In the span of a little over two years, Santos claimed he had acquired an apartment in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil worth between $500,000 and $1 million. He accumulated more than $1 million in his savings account and at least $100,000 in his checking account. He incorporated in Florida a New York City-based consulting firm called the Devolder Organization LLC, in which he claimed a 100% interest worth between $1 and $5 million. His annual salary there was $750,000 and his “Unearned” income – based on dividends from the company – was between $1 million and $5 million. He also went from having no declared assets in 2019 – as reported in his May 11, 2020, financial disclosure report – to assets ranging from $2.6 million to $11.3 million in his 2022 financial filing. His financial situation went from meager to materially substantial virtually overnight.

Excerpts from Santos’s financial disclosure report to Congress filed on September 6, 2022, are pasted below.

This sort of unexplained financial bonanza in such a relatively short period of time should have set off investigative alarm bells.

Pay Thyself

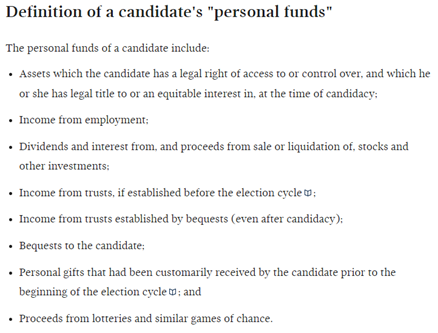

Odd personal financial dealings can also signal potential character issues and shortcomings in trustworthiness. According to the FEC, candidates for federal office are permitted to use unlimited amounts of their own “personal funds” for campaign purposes. There are also no limits on “loans” made from candidates’ personal funds to their campaigns. In addition, a candidate may choose to forgive “all or a part of a loan from his or her personal funds to the campaign.” However, a candidate must file a signed statement indicating that he or she forgives the loan.

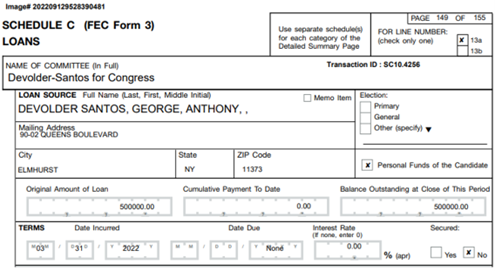

Santos, according to his FEC disclosures, during his 2020 and 2022 election races personally loaned his campaigns a total of $786,250. Red flags were apparent in these disclosures early on that should have drawn more scrutiny. On March 31, 2020, he personally loaned his campaign $50,000, nearly his entire salary from the previous year. Additional loans for that election totaled $31,250, eclipsing his entire 2019 salary. His personal loans to his campaign during the 2022 campaign increased dramatically to $705,000, nearly matching his claimed salary of $750,000, as reported in his September 2022 financial disclosure report to Congress.

The FEC defines personal funds this way:

For the $81,250 Santos loaned his campaign during the 2020 election, his campaign repaid him $31,200 in November and December 2020. So far, his campaign has not repaid any of the $705,000 Santos personally loaned his campaign for the 2022 election. An example of the FEC records citing the “personal funds” that George Santos loaned to his campaign is provided below.

A $199.99 (Miraculous) Coincidence

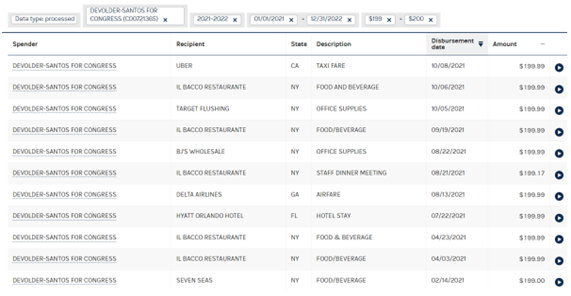

Sometimes records speak volumes through their omission of details or simply their unlikely veracity. According to records filed with the FEC between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2022, the Devolder-Santos for Congress campaign listed 37 separate expenses for exactly $199.99, without any reasonable accounting. These purchases included an office supply run to Staples on December 27, 2021, and also on the following day. Each purchase totaled $199.99.

Two separate shopping trips to BJ’s Wholesale two months apart in August and October 2021 cost exactly $199.99, as did three trips to Best Buy over a four-month period.

Despite the fact that the price of airline tickets frequently fluctuates due to gas prices and other factors, four separate flights on Delta Airlines from August to December 2021 each cost the Santos campaign exactly $199.99. From October to December 2021, the campaign reported five separate Uber rides, all in California, that each cost exactly $199.99. Miraculously, Santos campaign officials also appear to have ordered the same items from the menu when they frequented the Il Bacco Restaurant on Northern Blvd. in Little Neck, Queens, in Santos’ congressional district seven times, with each visit producing an expenditure of precisely $199.99.

As Politico reported in January 2023:

Campaigns rack up millions of dollars in expenses and thousands of line items per campaign, but it is rare for them to notch even one $199 expense, according to a POLITICO review of campaign finance records. FEC data shows more than 90 percent of House and Senate campaign committees around the country did not report a single transaction valued between $199 and $199.99 during the 2022 election cycle.

Santos reported 40 of them.

In fact, his campaign accounted for roughly half of all expenses by all campaigns that cost exactly $199.99 — a statistical improbability.

In listing these amounts, Santos evaded the FEC’s requirement regarding documentation for these expenses because they fell under $200 by a single penny, as outlined here:

A sampling of the $199.99 expenses reportedly incurred by the Santos campaign that they reported to the FEC are provided below.

This is the first of three posts examining how a diligent review of public records could have shed light on questionable behavior by George Santos and raised serious questions about his veracity before the November 2022 election.